… the shadow (sayah) has an importance in the non-material world (ghayr-i madi)… etymologically, the shadow (sayah) has the meaning of the double (ham-zad), and shadow-stricken (sayah zadah), and Jinn-stricken or possessed by jinn (jinn giriftah); and it also refers to a spiritual essence (sirisht-i ruhani), which appears in a material body (heykal-i madi). It has also been called fantôme ombre.

—Sadeq Hedayat1Sadeq Hedayat, Majmūʻah-i asār-i Sādiq Hidāyat: pazhvahish dar farhang-i ‘āmīyān-i mardom-i Īrān [Complete Works of Sadegh Hedayat: Studies on the Folklore of Iran], vol. 3 (Kālīforniyā: Korūh-i Intishārāt-i Āzād-i Īrān, 2018), 326. My translation from the Persian.

Those who wander in the night (nykti polois): Magi (magois), bacchants (bakchois), maenads (lênais), initiates (mystais).

—Heraclitus2Heraclitus (Fragment 14 B), cited in Jan N. Bremmer, “Persian Magoi and the Birth of the Term ‘Magic,’” in Greek Religion and Culture, the Bible and the Near East (Leiden: Brill, 2008), 236; Hedayat was deeply interested in the history of Magic in Iran and wrote an article in this connection in French, ‘La Magie en Perse’ [Magic in Iran]. See Hedayat, Complete Works of Sadegh Hedayat – Volume III, 373-385.

The origin of the cinema lies in the ancient tradition of shadow-play and the delight in shadows, in popular sorcery, and magic. The beginnings of the invention of the cinematograph in the late nineteenth-century is linked with the history of magic lantern shows, and “one of the leading precursors to horror cinema was the Phantasmagoria, a form of magic lantern presentations that specialized in raising ghostly specters.”3Stacey Abbot, Celluloid Vampires: Life After Death in the Modern World (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2007), 45. Indeed, the “magic lantern was an instrument of natural magic that kept its ‘magical’ character longer than almost any other…” optical media, and it never truly disappeared but when it was transformed by incorporating motion and when it “became the cinema, its first achievement was not to produce art, but to put stage magic out of business.”4Thomas L. Hankins, and Robert J. Silverman, Instruments and the Imagination (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995), 69. Hence, horror cinema almost simultaneously appears with the cinema itself, when the French magician Georges Méliès projected the first cinematic vampire: Le manoir du diable (The Haunted Castle; 1896). It is strange, then, that a people whose name is indelibly linked with magic, the famed Magi—derived from the Greek word for Persian priests, magoi and Latinized as magus—should come so late to the magic art of horror cinema.

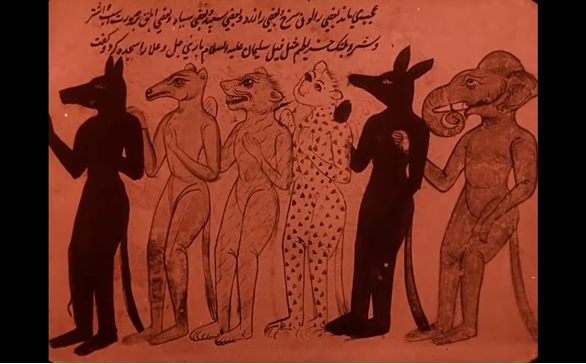

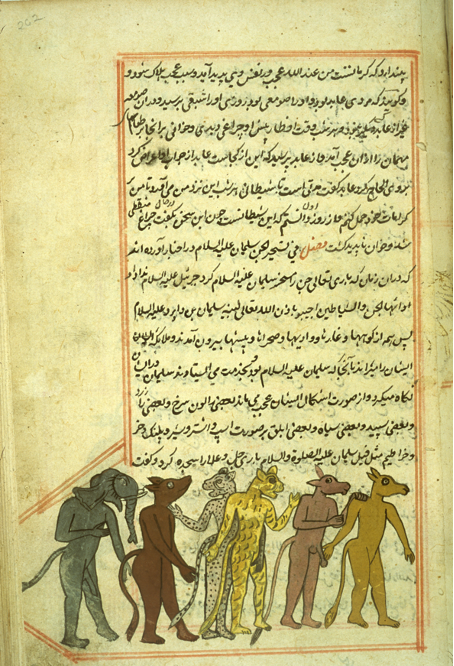

And yet, it seems from its early beginnings horror cinema and Persian magic were indelibly linked together in the Western cultural imaginary. Indeed, although horror cinema may be considered to have emerged together with the invention of cinema itself, yet it is in the year 1922 that the chiaroscuro light of horror cinema shed its luminous darkness into the world with the production of the German expressionist masterpiece, Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (dir. F. W. Murnau, 1922). The same year gave birth to another horror film of resplendent darkness that equally cast a lasting spell on the imagination of audiences, the Swedish-Danish horror documentary, Häxan (The Witch; 1922), directed by Benjamin Christensen.5On the film see Richard Baxstrom and Todd Meyers, Realizing the Witch: Science, Cinema, and the Mastery of the Invisible (New York: Fordham University Press, 2016). It is in one of the first images of Häxan that we encounter an image drawn from a Persian manuscript containing images of monstrous and supernatural creatures. The intertitle states: “In Persia, the imaginary creatures depicted in the following picture were thus believed to be the cause of diseases.” Then through the technique of an iris out we get the image of the manuscript, but the source of the image remains undisclosed. What is this mysterious Persian manuscript and the monstrous figures that it depicts? The manuscript page is drawn from a Persian translation of a famous compendium of so-called ‘natural history’ in Arabic called, ‘Wonders of Created Things and Strangeness of Existent Beings’ (‘Ajā’ib al-makhlūqāt wa gharā’ib al-mawjūdāt) by the thirteenth century Persian naturalist scholar, jurist and cosmographer Abū Yahyā Zakarīyā’ ibn Muhammad al-Qazwīnī (d. 1283). The ‘Ajā’ib or wonders/marvels is a term that designates an important genre in Arabic and Persian literature that “dealt with all things that challenged human understanding, including magic, the realms of the jinn, marvels of the sea, strange fauna and flora, great monuments of the past, automatons, hidden treasures, grotesqueries and uncanny coincidences.”6Tales of the Marvellous and News of the Strange [al-hikayat al-‘ajiba wa’l-akhbar al-ghariba], introduced by Robert Irwin, trans. Malcolm C. Lyons (UK: Penguin Books, 2104), ix. Qazwīnī’s compendium is the most famous example of this genre and combines discussions on botany, zoology, minerology, “geography, astrology, talismans, and alchemical transmutations with accounts of angels, jinn, and savage beasts at the edges of the known world.”7Travis Zadeh, Wonders and Rarities: The Marvelous Book That Traveled the World and Mapped the Cosmos (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2023), 3. An excellent and definitive study of Qazwīnī’s text. The manuscript page and image in Häxan therefore does not directly refer to imaginary creatures that were “believed to be the cause of diseases,” but is an account of Solomon’s theurgic control and command of the jinn. In this strange or weird (‘aj’ib) way, at least, there is a short-circuit between early horror cinema and Persian magic.8An argument may be made as to the possible Orientalizing gesture in the evocation of this reference to ‘Persia’ in the film, especially in the way Persian magic conjures up images of a ‘superstitious Orient’ in the Western cultural imaginary. But there is also another fantasmatic ‘Orient,’ in which ‘Persia’ and the Iranian prophet ‘Zoroaster’ were often associated with magic, an association that goes back not only to the occult philosophy of the Renaissance and what was termed prisca theologia, but even further back to ancient Greece, to pre- and post-Socratic philosophers who saw ‘Persia/Zoroaster’ as the fount of primordial wisdom and which John Walbridge has termed ‘Platonic Orientalism.’ See John Walbridge, The Wisdom of the Mystic East: Suhrawardi and Platonic Orientalism (New York: State University of New York Press, 2001).

Image from Häxan (The Witch; 1922)

‘Six animal-headed demons or jinns, from ‘Ajā’ib al-makhlūqāt wa-gharā’ib al-mawjūdāt (Marvels of Things Created and Miraculous Aspects of Things Existing) by al-Qazwīnī (d. 1283/682). The copy was made in 1537/944, probably in western India. Neither the copyist nor illustrator is named.’ From The Islamic Medical Manuscripts at the National Library of Medicine. www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/arabic/natural_hist3.html

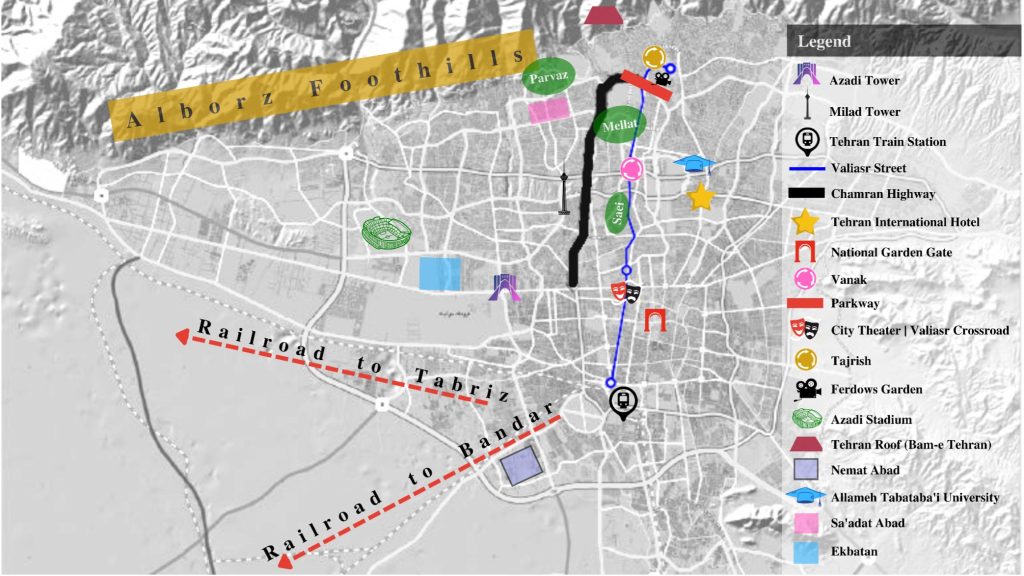

Theorizing the development of genre filmmaking in the history of Iranian cinema remains a desideratum, not least the horror genre, which had not gained popularity in Iran until more recently. Among the various genres that populate Iranian commercial cinema such as comedies, crime thrillers or melodramas, there is a paucity of examples of the horror genre and in the history of Iranian cinema more broadly. Indeed, a small number of horror films had been made in Iran in the Pahlavi era and in the post-revolutionary period under the Islamic Republic. However, as I will demonstrate, examples of films coded with horror elements and conventions may retrospectively be read in films which were not formerly regarded as encoded with formal or narrative features of horror. Finally, I will argue that there is a burgeoning of Iranian horror films after the 2009 failed protest movement in Iran (the so-called Green Movement), that may be termed, New Iranian Horror, which includes examples of transnational or diasporic horror films, that deploy the horror genre as a way to critique the socio-political conditions of post-2009 Iranian society.

There is no theorization of horror films in Iran and no academic studies of the history of Iranian horror cinema have ever been written, since most scholars of Iranian cinema consider that the horror genre never found a foothold among Iranian filmmakers for various reasons. Among the reasons often provided for the shortage of horror films in Iran is censorship, or that it is “partly due to the infamous censorship rules.”9Farhang Erfani, Iranian Cinema and Philosophy: Shooting Truth (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 7. However, the censorship rules that scholars often refer to were instituted after the 1979 Iranian Revolution, and although censorship existed in the Pahlavi era, it does not explain the paucity of horror films in the pre- and postrevolutionary era. Some Western scholars have even erroneously claimed that since “Iranian horror films are subject to censorship in the country,” they “are consequently an exilic or diasporic phenomenon.”10Terri Ginsberg and Chris Lippard, Historical Dictionary of Middle Eastern Cinema (London: Rowman & Littlefied, 2020), 212. This mistaken view is partly due to the fact that many of the horror films made in Iran were part of Iran’s commercial cinema and were never seen outside Iran, and those Iranian films that were seen outside Iran were prestige art house films or New Wave films sent for competition to International Film Festivals, both in the pre and post-revolutionary period. Hamid Naficy theorizes that the underdevelopment of the horror genre in Iranian cinema is due to cultural schemata that are specific to Iran such as the logic of ‘ritual courtesy’ (taʻāruf):

It seems the case also that the absence of certain film genres in a culture may be explained by the unacceptable violation of cultural schemas that these genres produce. One reason for the underdevelopment of the horror genre in Iranian cinema, for example, may be sought in this genre’s violation of the etiquette of formal relationships between strangers dictated by the system of ritual courtesy, which requires control of emotions and display of ritual politeness. This system authorizes, even encourages, the display of certain emotions such as sadness but it prohibits behaviors such as frightening someone, rage, and graphic violence against women and children—which are the staples of the horror genre.11Hamid Naficy, The Making of Exile Cultures (University of Minnesota Press, 1993), 237.

Although Naficy’s theory that the underdevelopment of the horror genre is the result of cultural schemas such as its contravention of the system of ritual courtesy operative in Iranian culture is largely apt, yet I would suggest that a more unconscious dimension is operative and hence a psychoanalytic reading of Iranian society and horror cinema provides a unique theoretical lens for understanding the early underdevelopment of this genre in Iranian cinema, and its recent renaissance. Indeed, the horror genre is the site of what is repressed within the psyche and brings out the repressed content to the surface and exposes it. The horror genre is the privileged domain of psychoanalytic film theory, especially due to the genre’s relation to the unconscious, to Freud’s concept of the uncanny (unheimlich) (meaning ‘unhomely’ in the original German), and to the logic of repressed desire or the return of the repressed. There is a correlation between Iranian society as a ‘repressed’ society and a lack of horror in the development of Iranian horror; but since horror cinema is often the site of the ‘return of the repressed,’ the rise in popularity of the horror genre in contemporary Iranian cinema therefore signals the emergence of the return of the repressed, especially as the unconscious fears, anxieties, deadlocks, antagonisms and contradictions in Iranian society and psyche are brought to the surface and exposed in these films.

Besides the problematic of defining and discussing horror in the history of Iranian cinema, scholars have long acknowledged that the horror genre itself is notoriously difficult to define and conceptualize, not least because “genres are never fixed.”12Brigid Cherry, Horror (New York: Routledge, 2009), 2. Indeed, throughout the long history of film, conceptualizing horror has posed a problem not only in Hollywood cinema, but in global cinematic traditions. Mark Jancovich has pointed to several problems in the history of the theorization of horror, given that many of the films that were included in academic histories of horror were not originally conceived, produced, or received as horror films, and were “defined as horror only retrospectively.” Indeed, Jancovich notes that there is often a slippage between the term horror and terms such as fantasy, the Gothic, and the tale of terror,” which are terms that are not “commensurate with one another but through which differences can be elided.”13Mark Jancovich, “General Introduction,” Horror, the Film Reader (London: Routledge, 2001), 7-8. This slippage between seemingly incommensurate terms such as fantasy, Gothic, and tale of terror, “highlight a problem about generic definitions.” For example, in these histories the work of silent filmmakers such as Georges Méliès were retrospectively viewed as horror, although “it is not at all clear that these films were originally understood as horror films.”14Jancovich, “General Introduction,” 7. Similarly, films that today may not be thought of as horror were originally produced and marketed as horror films at the time of their release. As Brigid Cherry puts it, “deciding on a classification as to what film (or kind of film) is (or isn’t) a horror film” is not “straightforward,” and “what might be classed as the essential conventions of horror to one generation may be very different to the next…”15Cherry, Horror, 2. In this sense, the Freudian concept of ‘retroactivity’ (Nachträglichkeit) (developed by Freud in Studies in Hysteria and the Entwurf, and later in the “Wolf-Man case) as a form of recursive temporality in which an event in the past only becomes traumatic retroactively may be a useful concept here, since it signals a belated understanding or retroactive attribution of horror elements to earlier films that were not regarded as horror or containing elements of horror originally.

In the first Pahlavi era (1925-1941) American and European horror imports dominated the cinemas, with no indigenous productions of Iranian horror films. Indeed, there was state resistance to the screening of American horror films, as well as resistance from modernist intellectuals at the time who deemed horror films a corrupting influence on children and youth and as a source of moral corruption in society.16Jamal Omid, Tarikh-i Cinema-yi Iran: 1279–1357 (Tehran, Iran: Intisharat-i Ruzanah, 1998), 99. See also, Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 1: The Artisanal Era, 1897-1941 (Duke University Press, 2011), 246. Iranian intellectuals were caught in a paradoxical predicament since they wanted to introduce Western media into Iranian society as soon as possible, but they also opposed action and horror films, arguing that European and American horror films were produced for the lower classes and “did not answer Iran’s needs, but would rather pose a threat to the progress and reform of Iranian society.”17Bianca Devos, “Engineering a Modern Society? Adoptions of New Technologies in Early Pahlavi Iran,” in Culture and Cultural Politics Under Reza Shah: The Pahlavi State, New Bourgeoisie and the Creation of a Modern Society in Iran, ed. Bianca Devos and Christoph Werner (New York: Routledge, 2014), 276. Indeed, modernist authors and intellectuals “agreed that, above all, horror films could bring mental harm to young spectators.”18Devos, “Engineering a Modern Society?” 276. In this way both the state and modernists agreed as to the pernicious effects of horror films on young minds and on society at large and this did not only limit the import of horror films from America and Europe but may be one of the reasons for the lack of Iranian horror productions during this period.

By the middle of the second Pahlavi era (1941-1979) two types of filmic productions became dominant in Iran: an Iranian commercial cinema called filmfarsi and an art house movement called the Iranian New Wave (mauj-i naw). The first was the popular commercial cinema pejoratively called filmfarsi (Persian film) by critics, consisting mostly of stew-pot melodramas (ābgūshtī) or tough-guy films (lūtī or jāhilī), largely song and dance films or melodramas influenced by Hollywood, Egyptian and Bollywood Indian films. The second was art cinema or the Iranian New Wave (mauj-i naw) that developed at the end of the 1960s and the 1970s as a reaction to the earlier filmfarsi films and which was influenced by the aesthetics of Italian Neorealism, with rural settings, non-professional actors, and often with a subversive critique of socio-economic conditions and the political climate of the Pahlavi regime.

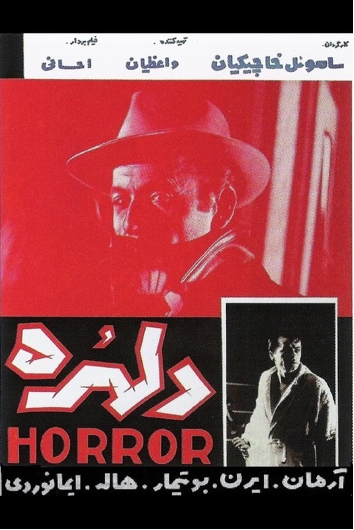

Although it is generally noted among scholars of Iranian cinema that the horror genre never gained traction in the history of the development of cinema in Iran, nonetheless elements of horror were present in individual films within Iran’s commercial cinema early on, largely beginning in the second Pahlavi era. Among the most important filmmakers during this period whose name is indelibly linked with crime thrillers—especially inflected through the influence of German expressionist cinema, film noir and Alfred Hitchcock—is the Armenian-Iranian Samuel Khachikian (1923-2001). Indeed, Khachikian, dubbed the Iranian Hitchcock, was the first filmmaker in the history of Iranian cinema to terrify audiences with his crime thrillers, imbued as they were with a sense of mystery, fear, and suspense. Khachikian’s contribution to the genre was not simply to develop expressionist and noir techniques in his thrillers with an unmistakable Iranian stamp but to simultaneously deploy formal codes of the horror genre in several of his films.

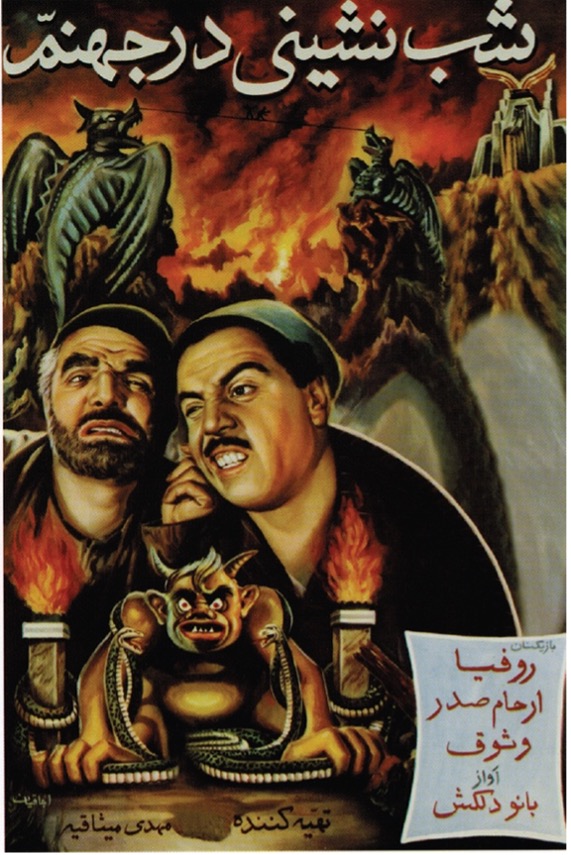

Among his films that may be seen inflected with generic codes and conventions of horror is Anxiety also known as Horror (Dilhurah, 1962) and Delirium (Sarsām, 1965), including the highly popular hybrid subgenre comedy-horror film, A Party in Hell (Shabʹnishīnī dar jahanam, 1956). It is the story of a loan shark Haji Agha, who spends a night in hell, and encounters several literary, cinematic, and historical figures, including Hitler. The film may be considered as a “Persianized take on Dickens’s A Christmas Carol.”19Abbas Amanat, Iran: A Modern History (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2017). Another film that is worth mentioning in the context of horror is Khachikian’s Zarbat (Strike, 1964), which, although it is ostensibly a crime thriller—the mise-en-scène in which, especially the low-key and chiaroscuro lighting in the film—often evokes elements of gothic horror and German expressionism by way of film noir. Indeed, in Khachikian’s noir cycle, comprised of Delirium, Anxiety, and Strom in Our City (1964), the home and domestic interiors are encoded with horror motifs drawn from the gothic universe that “evoke the uncanny of psychological horror while still providing a setting for the professional activities of criminal gangs and detectives.”20Kaveh Askari, Relaying Cinema in Midcentury Iran (California: University of California Press, 2022), 151. It may be said that Khachikian’s combination of film noir with horror elements at once brings to the surface the societal repressed (film noir) and what is repressed within the psyche (horror genre).

Party in Hell (1956) from M. Mehrabi, Sad va panj sāl iʻlān va pūstir-i fīlm dar Īrān (Tehran: Nazar Publishers, 1393/2014), 68.

Recently Khachikian’s crime cinematic universe has been recognized to be coded with elements of the horror genre by Laura Fish, who reads Khachikian’s crime thrillers in a comparative context with Edger Allen Poe’s gothic tales, a felicitous choice since Poe was effectively the inventor of the detective story or crime genre. Fish reads Poe’s tales and Khachikian’s crime thrillers by looking at the presence or absence of a corpse “as a critical device inciting the horror logic that hinges on the centralization and devolution of female characters.” Deploying Freud’s psychoanalytic concept of the uncanny and Julia Kristeva’s concept of abjection in relation to the present or missing corpse, Fish “positions Khachikian’s production of horror as a gendered process of feminine descent into madness and eventual masculine salvation.”21Laura Fish, “The Disappearing Body: Poe and the Logics of Iranian Horror Films.” Poe Studies 53 (2020): 88. In this reading these films become invested with psychological horror, especially in the way in which horror stages the dynamics of gender and sexuality in the psyche and in society. Khachikian’s comparison to Poe is certainly apt, yet Hitchcock would seem to be a more exact comparison apropos the logic of the corpse, as Hitchcock himself states in a humorous turn, “If I was making ‘Cinderella,’ everyone would look for the corpse. And if Edgar Allan Poe had written ‘Sleeping Beauty,’ one would look for the murderer.”22Hitchcock On Hitchcock: Selected Writings and Interviews, ed. Sidney Gottlieb (California: University of California Press, 1995), 145.

Horror (1962) from M. Mehrabi, Sad va panj sāl iʻlān va pūstir-i fīlm dar Īrān (Tehran: Nazar Publishers, 1393/2014), 80.

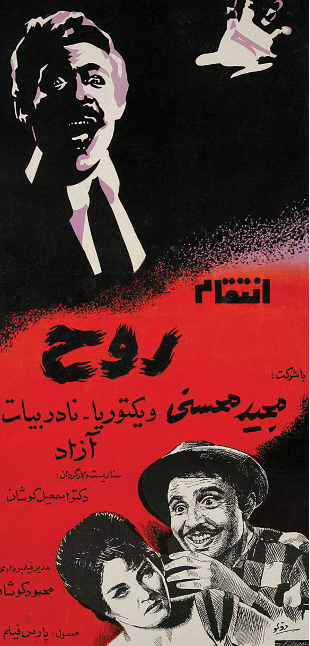

Several commercial horror films were made during the second Pahlavi era such as vampire and supernatural ghost films, mostly B-movies that were unsuccessful with audiences of the time, and although influenced by Euro-American horror and Gothic genres, nevertheless had an indelibly local flavor. B-horror vampire films were not unknown in the second Pahlavi era, and one of the first examples of vampire cinema in Iran is the largely derivative commercial film, Zan-i khūn āshām (The Female Vampire; 1967) directed by Mustafa Usku’i, which had a female lead as a vampire.23Mehrabi, Tarikh-i sinima-yi Iran, 120. Among examples of commercial supernatural ghost films is the horror-comedy Intiqām-i Rūh (Revenge of the Ghost; 1962) directed by Esmail Koushan (1917-1983)—one of the pioneering figures of Iranian cinema—around the same period. The film is about a wealthy man with a young son who is murdered by his brother so that the latter can possess his riches. After his murder, his son becomes homeless and his ghost vows to take revenge against his cruel brother and to haunt the mansion until he finally rediscovers his son and exacts revenge. The film was influenced by the aesthetics of Khachikian’s films and is coded with Gothic tropes and expressionist techniques and is an example of commercial Iranian horror genre of the period.24On the films and place of Esmail Koushan in the history of Iranian cinema see Nima Hassani-Nasab, “A Hollywooder in the Land of Persia,” trans. Philip Grant, Underline: A Quarterly Arts Magazine 2 (February 2018): 94-9.

Revenge of the Ghost (1962) Nima Hassani-Nasab, “A Hollywooder in the Land of Persia,” translated by Philip Grant, Underline: A Quarterly Arts Magazine 2 (February 2018), 94.

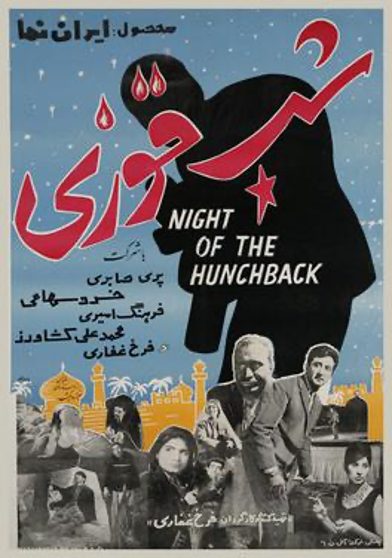

The logic of horror articulated by Fish apropos the presence or absence of a corpse in Khachikian’s crime thrillers appears in other films during the same period. Indeed, this dialectic of the absence and presence of a corpse is also operative in Farrokh Ghaffari’s early precursor to the Iranian New Wave, Shab-i qūzī (Night of the Hunchback; 1963), based on a story from the Thousand and One Nights. The film is a “dark comedy” containing expressionist elements “about a hunchback in a team of entertainers, who dies in a farcical accident, and his dead body is passed around from person to person.”25Michele Epinette, “ḠAFFĀRI, FARROḴ,” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, 2015, available at www.iranicaonline.org/articles/gaffari-farrok (accessed on 05 October 2015). The problematic of how to get rid of the corpse, which appears and disappears throughout the film, functions similarly to the corpse in Alfred Hitchcok’s The Trouble with Harry (1955). Ghaffari’s film not only “reveals the corruption, hypocrisy, and fear in the different classes of Tehran society…”26Epinette, “ḠAFFĀRI, FARROḴ.” at the time, but especially the unconscious fear and anxiety in a society where critics and dissidents of the State feared the Shah’s secret police, SAVAK.

Night of the Hunchback (1963)

Although a large number of horror films or horror inflected films were part of the commercial filmfarsi, there are also examples of New Wave films that contained elements of horror, or that may be read retroactively as coded with certain narrative or formal features of horror. Among these art films that may be read retroactively as coded with elements of horror—particularly in their formal features—is Mohammad Reza Aslani’s magnificent Shatranj-i bād (Chess Game of the Wind; 1976), which was recently rediscovered and restored. The film has Gothic and expressionist motifs and is about the saga of the declining fortunes of a Qajar family—like Luchino Visconti’s familial epic The Leopard (1963)—at the centre of which is again a corpse, hidden in a cellar. All the interior shots of the film were lighted solely by candles and exemplify a masterful command of expressionist cinematography and chiaroscuro lighting by the great Iranian cinematographer Houshang Baharlou. Although the interior lighting evokes Stanley Kubrick’s similarly candle-lit interiors in Berry Lyndon (1975), Aslani has cited the works of the French Baroque painter Georges de La Tour (d. 1652), and especially the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century painter and poet Mahmoud Khan-i Saba (aka Malek-o-Shoara), whose expressionist painting Estensakh (Transcription) was an inspiration for the candle lighting of the interior scenes.

Estensakh (Transcription) by Mahmoud Khan Malek-o-Shoara https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Estensakh_by_Mahmoud_Khan_Malek-o Shoara.jpg#/media/File:Estensakh_by_Mahmoud_Khan_Malek-o-Shoara.jpg

Screenshot from Chess Game of the Wind (1976)

Another New Wave film that may be read retroactively as coded with narrative and formal elements of horror, especially through expressionist lighting techniques, is Bahman Farmanara’s Shāzdah Ehtejab (The Prince Ehtejab; 1974) based on the 1969 story of the same name by Houshang Golshiri. The story is about the eponymous Qajar prince who is dying from tuberculosis. The film uses techniques of flashback and flashforward and real photographs of Qajar monarchs and their descendants to evoke a dead yet spectral past that still haunts the present. The eponymous prince, who harbours a sense of guilt from the cruelty of his ancestors’ misdeeds, is visited by ghostly apparitions of his father and grandfather who castigate him for not following in their footsteps of despotism and cruelty. It is as if “Ehtejab’s tuberculosis comes to synecdochically embody not just the fate of the aristocracy in modernity, but also the degradation of time as such, which the cinema has the unique capacity to arrest, preserve, and set back in motion.”27Pardis Dabashi, “The Art of the High-Born: A Look Back at Bahman Farmanara’s Shazdeh Ehtejab”, Politics / Letters, September 17, 2018, http://quarterly.politicsslashletters.org/the-art-of-the-high-born-a-look-back-at-bahman-farmanaras-shazdeh-ehtejab/ (accessed on 10 September, 2022). In this sense, Farmanara’s film at once evokes the medium of cinema as a purveyor of ghosts, the long dead who exist or persist only through the cinematic apparatus; and those in power or the elite, who eventually become the ghosts of history, and are reanimated as specters through the moving-image—the cinema. In this connection, even Jacques Derrida draws a link between psychoanalysis, spectrality and the cinema stating, “The cinematic experience belongs thoroughly to spectrality, which I link to all that has been said about the specter in psychoanalysis—or to the very nature of the trace.”28Antoine de Baecque and Thierry Jousse, “Cinema and Its Ghosts: An Interview with Jacques Derrida,” trans. Peggy Kamuf, Discourse 37, 1–2 (Winter/Spring 2015), 26. For Derrida, not only psychoanalysis, and psychoanalytic reading “is at home at the movies,”29De Baecque and Jousse, “Cinema and Its Ghosts,” 26. but “the projected film,… is itself a ghost.”30De Baecque and Jousse, “Cinema and Its Ghosts,” 27.

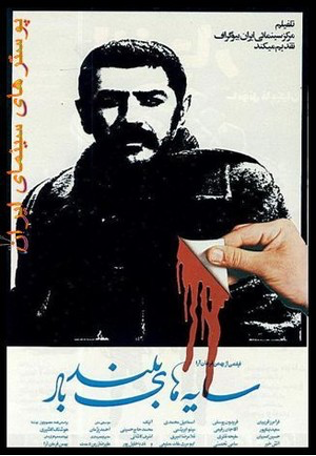

Perhaps one of the most important New Wave horror films of the pre-revolutionary era is Bahman Farmanara’s remarkable, Sāyahā-yi buland-i bād (Tall Shadows of the Wind; 1979). The film is based on a short story by Houshang Golshiri called “First Innocent,” and represents their second collaboration together after Prince Ehtejab (1974). The film centres on mysterious and supernatural events that take place in an unnamed village, metaphorically representing Iran. In a village, a group of superstitious inhabitants, who had erected a scarecrow clad in a black robe for protection are subsequentially terrorized by it and begin to believe in the supernatural powers of the scarecrow, and eventually worship it as a redeemer. The only people who do not believe in the supernatural power of the scarecrow is the main character, a bus driver named Abdullah and the village teacher. The film was made just before the 1979 revolution and deployed the codes and conventions of psychological horror and folk-horror, as a critique of the Pahlavi monarchy. The film was banned first by the Shah’s regime and later by Khomeini and the Islamic Republic. This is to be expected, as the film does not only represent a critique of the ruling political ideology of the Shah but also Shi’ite religious authority (clergy) and the belief in the expected Shi’ite savoir or the Twelfth Imam. In this sense, the figure of the scarecrow stands at once for religious (Shi’ite) and political authority (the Pahlavi State). Indeed, the films critique has a Marxist or communist revolutionary dimension, as Golshiri was a member of the Tudeh Party (Iranian communist party) for a short period, for which he was arrested and imprisoned for six months in 1962.31Mirʿābedini Ḥ. and EIr, Hušang Golširi [in:] Encyclopædia Iranica, vol. XI, fasc. 2, 114–118, www.iranicaonline.org/articles/golsiri-husang (accessed January 11, 2023). In the film the teacher of the village represents the Iranian intellectual and Abdullah, stands for the proletariat or the working class. In one of the last scenes of the film, this revolutionary dimension comes to the fore, as there is a powerful and surreal dream sequence in which Abdullah dreams that he and large group of villagers are donned in red clothing, and holding red flags and banners attack the black-clad scarecrows in the field and set them on fire.

Tall Shadows of the Wind (1979)

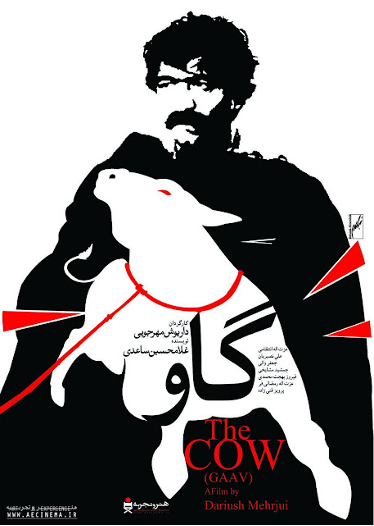

Among the Iranian New Wave films that can retroactively be read as containing elements of the horror genre broadly construed is Darioush Mehrjui’s Gav (The Cow; 1969), which blends neo-Gothic and expressionist elements with Italian neo-realism. The film’s story stages the mental deterioration of the farmer Masht Hassan (Ezzatolah Entezami), who after learning that his beloved bovine has died, slowly descends into madness and culminates by identifying with his cow. The film was based on a short story by the Marxist psychiatrist Gholam-Hossein Saedi (1936-1985), and has been variously interpreted in light of Iranian folklore, metempsychosis, etc. However, the film is open to a psychoanalytic reading, especially as exemplifying the structure of fetishism. Sigmund Freud famously considered that the “return of the repressed,” the repressed truth of a traumatic event, can appear either as symptom, or as fetish. A fetish is in a way the obverse of the symptom. If the symptom is the excess that perturbs the façade of false appearances, “the point at which the repressed Other Scene erupts, [then] the fetish is the embodiment of the Lie that enables the subject to sustain the unbearable truth.”32Slavoj Žižek, Enjoy Your Symptom! (London and New York: Routledge, 2008), x. Indeed, the cow functions as a perfect fetish for Masht Hassan, whose loss is so catastrophic that to recuperate the lost fetish he ultimately sacrifices his sanity and identifies with it. The cow as fetish enabled Masht Hassan to cope with his everyday existing reality by repressing the traumatic truth of the socio-political deadlock of the Pahlavi State, and the threatening and paranoiac atmosphere created by its secret police (SAVAK), symbolized in the mysterious and menacing figures of the Crystallines (Boluriha). This inaugural film of the Iranian New Wave has certain resonances and correspondences with aspects of New Iranian Horror films of post-2009 (see below), especially in its critique of authoritarian politics and the subsequent pervasive fear and anxiety in society.

The Cow (1969)

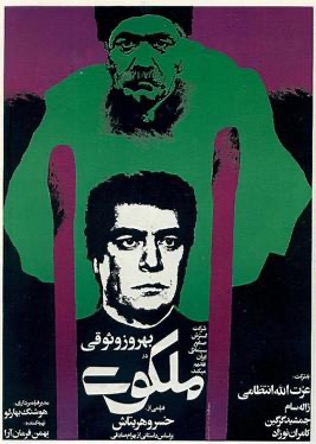

A New Wave film that didn’t simply contain elements of the horror genre but may be considered more fully as an example of art-house horror is the banned Malakūt (Heavenly Kingdom; 1976) by Khosrow Haritash, based on a 1961 novella of the same name by Bahram Sadeqi (1937-1985), and with Behrouz Vossoughi, perhaps one of the most famous actors of the pre-revolutionary era, in the lead role. The film centers on the figure of Mr. Maveddat who suddenly falls ill during a party in his garden and requires treatment. He is then taken to see a doctor called Dr. Hatam for treatment and is introduced to a mysterious man by the name of M. L., who has had parts of his body cut off over several years, and who has come to remove his last remaining limb, namely his hand. It is slowly revealed that Dr. Hatam harbours dark secrets and has killed all his pupils and previous spouses with a lethal injection—an injection that promises a long life full of earthly pleasures. In the end Dr. Hatam injects several people, including M. L. (Mr. Maveddat has cancer and will die soon regardless), and informs them that they will all die in a week. Dr. Hatam then goes to another city and begins anew his sinister plan.33See Saeed Honarmand, “MALAKUT,” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, 2011, available at www.iranicaonline.org/articles/malakut (accessed on 16 October, 2017).

Malakūt (1976)

Although ghostly and spectral figures at times appear in the New Wave cinema of Bahram Beyzaie—mostly drawn from Iranian mythological and epic sources such as Ferdowsi’s Shāhnāmah, or other texts such as the Memorial of Zarir, to name a few—his cinema has never been associated with horror. However, certain aspects of his films may be read retroactively as coded with elements of horror. For example, Beyzaie’s mysterious Gharībah va mih (The Stranger and the Fog; 1974), although permeated with mythological motifs, may retroactively be theorized and stylistically categorized as an instance of Iranian folk horror. Folk horror has been notoriously difficult to define among genre theorists, but Adam Scovell in his study Folk Horror: Hours Dreadful and Things Strange, provides one of the better definitions. In his book, Scovell offers an intriguing theorization in which narrative folk horror may manifest in cinema through what he terms “The Folk Horror Chain.”34Adam Scovell, Folk Horror: Hours Dreadful and Things Strange (UK: Auteur, 2017), 15. The folk horror chain is a “causational narrative theory” that consists of four rules or chains, with each link leading to the subsequent link in the chain. The four chains are: 1) a rural location or landscape; 2) isolation or isolated communities and groups; 3) skewed belief systems or morals; and 4) happening/summoning, usually through violent or supernatural methods.35Scovell, 17-19. The logic here is that a folk horror film must first be set in a rural setting, in a village, or in the countryside, where the landscape itself functions as a character in the story and contributes to the film’s formal style, evoking an atmosphere that is at times uncanny, surreal, or haunted. The Stranger and the Fog fulfils this requirement since the logic of rurality is operative in the film, it has a rural setting by the sea that establishes an important relation between the land or the earth (represented by Ra’na)—as well as between the sea or water (represented by Ayat)—, and the landscape creates a sense of surreality and the uncanny. The second category in the chain is that of isolated locations, and since in most folk horror the characters are isolated and cut off from any aspect of urban life, Beyzaie’e film again fits well into the second chain of folk horror, because the villagers in the film are completely severed from urban civilization and seem to exist as it were in mythic or primordial time. The third chain in the link, that of skewed belief systems or morals, suggests that characters in folk horror often have beliefs, rituals, and customs that are strange or alien to our modern sensibility, or to the dominant culture or religion. This logic is also operative in Stranger and the Fog, for the viewer of the film may find the rituals, customs, and practices of the village community strange, backward, or dangerous from their modern perspective. For instance, the custom in which Ayat must become part of the community by marrying one of the female villagers if he wishes to stay, or the ritual mourning performed in the beginning and end of the film, such as the final ritual mourning ceremony as Ayat goes back into the sea on the boat. Finally, as part of the fourth link in the chain, a violent or supernatural happening is also manifested in the film through the appearance of strangers who, like an otherworldly force, attack the villagers in the film’s final act. In this sense, Beyzaie’s The Stranger and the Fog may be considered the first folk horror film in the history of Iranian cinema.36Hamid Naficy has noticed elements of ‘horror’ in Stranger and the Fog, although not folk horror. He writes: “In Baizai’s Stranger and the Fog… the strangers’ entry into the primordial village follows the formula of American horror movies in the 1980s, in which a monster disturbs the stability and tranquility of a community and must be eradicated to return it to normal.” Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema Vol. 2, 344.

Stranger and the Fog (1976)

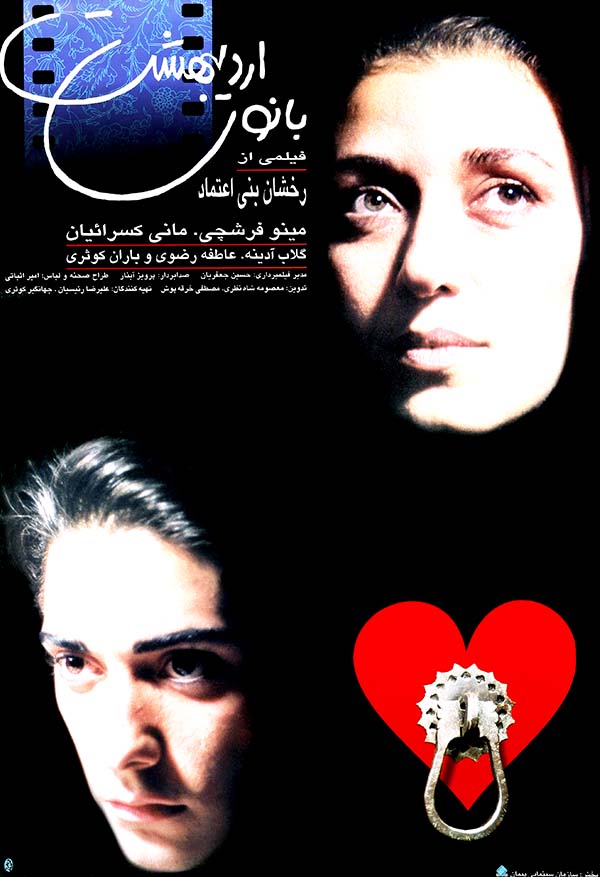

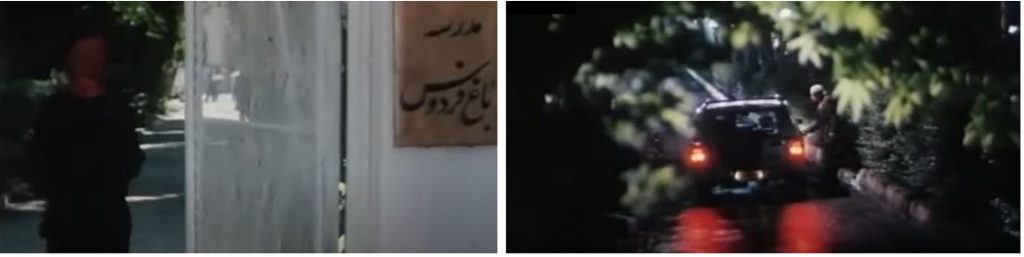

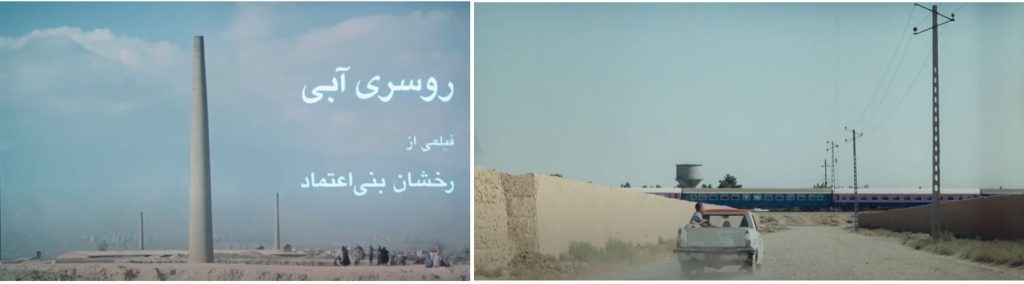

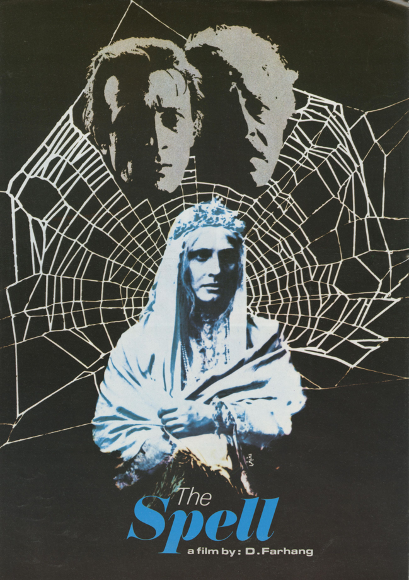

In the first two decades after the 1979 Revolution, two types of horror films may again be distinguished: on the one hand, lower quality productions, usually commercial horror films catered to Iranian audiences and not meant to be exported or seen outside Iran; and, on the other, higher quality films that aspired to be art films competing in international film festivals. Among the few pioneering higher quality horror films in the first decade of the post-revolutionary period that should be mentioned is Dariush Farhang’s Gothic Tilism (The Spell; 1988), starring the magnetic Susan Taslimi in her final role in Iran. The film is a Gothic tale set in nineteenth century (Qajar) Iran where the carriage of a newlywed couple breaks down during a storm, forcing them to seek refuge in a haunted mansion. As Fretting Botting states, Gothic atmospheres signal “the disturbing return of pasts upon presents”—elaborating that “in the twentieth century, in diverse and ambiguous ways, Gothic figures have continued to shadow the progress of modernity with counternarratives displaying the underside of enlightenment and humanist values.”37Fred Botting, Gothic (London and New York: Routledge, 1996), 1–2. In this Iranian Gothic film, the past that returns and haunts the present is one of the cruelties of Qajar kings that metaphorically stands for the atrocities of the clerics in the Islamic Republic. Among the commercial horror films of this period Hamid Rakhshani’s Shab-i bīst o nuhum (The 29th Night; 1989/1990) should be mentioned, which tells the story of a married couple Mohtaram and Haj Esmail. The film depicts an evil female spirit named Atefeh who haunts the mind of Mohtaram. The evil female spirit in the film—called Āl, a supernatural creature in Iranian folklore that personifies perpetual fever, and one that has been described as a child-stealing witch or demon38A. Shamlu and J. R. Russell, “ĀL,” Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. I, Fasc. 7, 741-42, accessed September 12, 2015, www.iranicaonline.org/articles/al-folkloric-being-that-personifies-puerperal-fever—appears as a nocturnal chador-clad figure in dark silhouette atop the roof of Hossein’s home. The film deploys Iranian folklore, the supernatural and occult motifs, and an arsenal of horror genre conventions to terrify its audiences. It was immensely popular among young Iranian audiences at the time and demonstrated a growing appetite for horror film productions.

University Archives, Northwestern University Libraries. “The Spell,” Hamid Naficy Iranian and Middle Eastern Movie Posters Collection Accessed Sun Mar 05 2023. https://dc.library.northwestern.edu/items/706318b6-254c-4a21 abed-a6b177461657

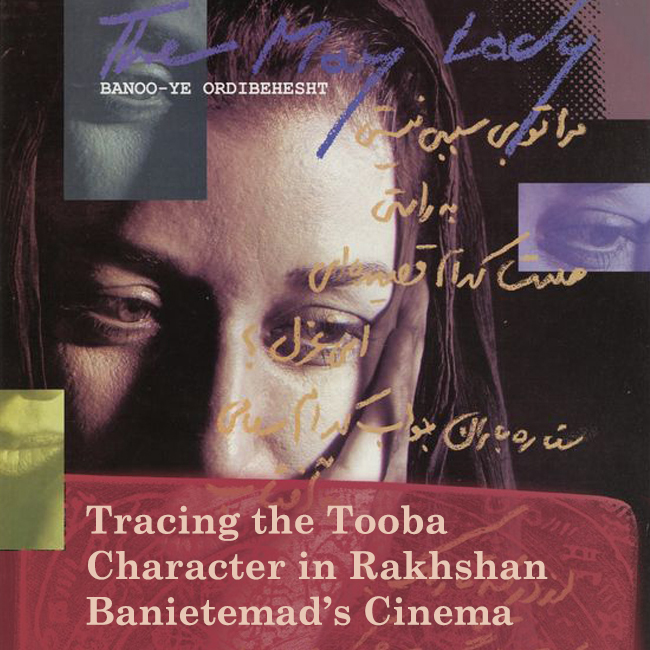

During this period, Islamicate folklore, the supernatural, and occult motifs were deployed more consistently as source material for horror films in Iran; and since some of this material was related to what is often termed “women’s Islam,” they provided ready material for exploration of horror themes. One example of horror genre films made in this vein is Mohammad Hoessein Latifi’s successful Khābgah-i dukhtarān (Girl’s Dormitory, 2004). The film deploys “popular Muslim beliefs and practices where a young woman becomes the target of a crazed killer claiming to be under the command of the jinn.”39Pedram Partovi, “Girls’ Dormitory: Women’s Islam and Iranian Horror,” Visual Anthropology Review 25, 2 (2009): 186–207. Pedram Partovi provides an excellent reading of the film and argues that the theological and legal difficulties facing the film were sidestepped by associating such “superstitious” beliefs (such as jinn and possession) with women, and thereby continuing the discourse on “the pivotal and deleterious female role in their practice and promotion.” As Partovi notes, such folk beliefs, though they may have accounted for the popularity of the film among female audiences, what Girls’ Dormitory also provided was a novel and satisfying form of female representation and identification that appealed to female audiences at the time, since it depicted “…its young female hero engaging with the visible and invisible barriers to individual and familial prosperity”40Partovi, “Girls’ Dormitory,” 187. in Iran at the time.

New Iranian Horror (Mauj-i naw-yi vahshat)

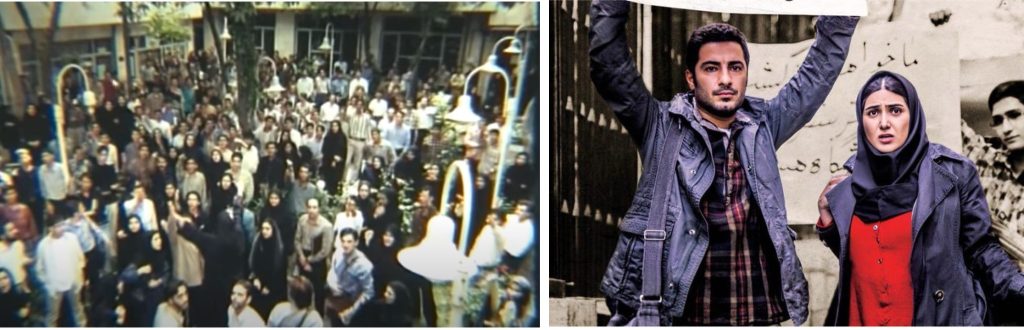

A new group of horror films have emerged in the aftermath of the 2009 presidential election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad which spawned mass protests in Tehran. These films deploy certain conventions of the horror genre as a politically subversive critique of the claustrophobic, terrifying, and paranoiac atmosphere of post-2009 Iranian society. Due to the censorship restrictions imposed on Iranian filmmakers, especially in the depiction of violence, blood, gore, and various other elements that are the staples of horror, filmmakers have had to creatively work around these restrictions while seeking to produce horror films. I have theorized the emergence of a band of horror films or horror inflected films that are structured around what I call the Uncanny Between the Weird and the Eerie, since staging horrific and terrifying scenes cannot directly be shown on screen.41Farshid Kazemi, “Interpreter of Desires: Iranian Cinema and Psychoanalysis” (PhD diss., University of Edinburgh, 2019), 186-226. The prestige horror films coming out of Iran and their transnational or diasporic counterparts in the past decade or so may be considered as having inaugurated what can be called New Iranian Horror. I draw a theoretical short-circuit or correlation between the two modes of the weird and the eerie (as theorized by Mark Fisher) to literary terms found in Perso-Arabic literature, particularly in texts such as the One Thousand and One Nights (Alf layla wa-layla) called ‘ajīb va gharīb (‘ajib, lit. meaning wondrous, marvellous or amazing; and gharīb, meaning, strange or weird). It should be recalled that there is no doubt that the translation of the One Thousand and One Nights into French by Antoine Galland in the period spanning 1704-1717 immensely influenced Euro-American literature, and especially the Gothic genre—not to mention the works of Edgar Allen Poe—all of which contained much of the themes and motifs that appeared in the Nights. And it is in the Gothic genre that we have the origins of the vampire and of vampire cinema itself.

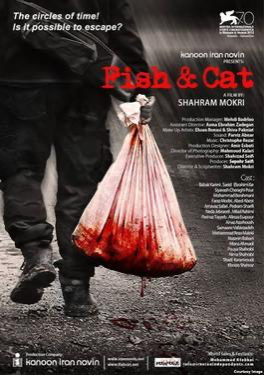

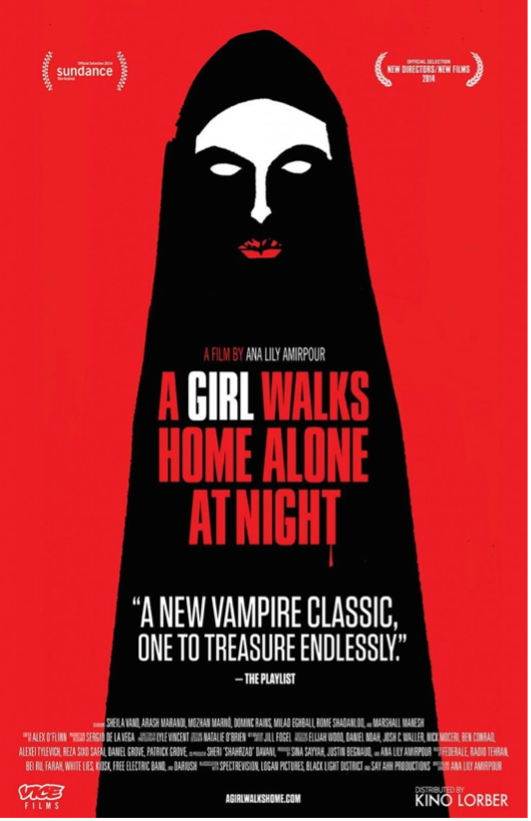

What distinguishes and characterizes the films of this new filmic horror renaissance that I have theorized through the two modes of the weird and the eerie is their evocation of the menacing environment of post-2009 Iran (which includes diasporic or exilic films) and several thematics that they commonly share. For example, among the various components shared by this movement are such motifs as political and ideological critique through the deployment of supernatural elements or occult phenomena (the devil/satan, vampires, jinn, Āl and zār, etc.). They also touch on such taboo subjects as (female and male) sex/sexuality, homosexuality, or queerness in Iran. They are often pervaded by doubles or doppelgängers (ham-zad, in Persian), dreamlike worlds, nightmarish landscapes, paranoid and menacing atmospheres, invisible threatening forces, and a sense of pervading fear, terror, or of impending doom. Some of these thematics appear in the films’ form or style which shares certain formal features with the universe of German expressionism and film noir, and that includes such techniques as contrast of light, dark, and shadows; the evoking of a sense of mystery, dread, existential angst, moral corruption and crime; these latter are evident especially in the films’ use of color, light, and darkness (low-key or chiaroscuro lighting); the mise-en-scène, setting, objects, and spaces; and camera techniques such as strange unbalanced (tilted) off-angle shots (Dutch angle) or oblique angle shots, long takes, extreme long takes, and even the entire film as a single take (especially in Shahram Mokri). The soundtrack or musical score of the films may also contain subversive Iranian underground music (Mokri’s Fish and Cat and Amripour’s A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night are emblematic in this respect). This is precisely why I consider these films as constitutive of a new movement, for beyond embodying the two modes of the weird and the eerie, they share a common set of motifs that evoke the menacing and suffocating atmosphere of post-2009 Iranian society.

Shahram Mokri’s Māhī va gurbah (Fish and Cat; 2013) may be said to have inaugurated the film movement that I have called the uncanny between the weird and the eerie, or the emerging New Iranian Horror. The film has been described by the director as an Iranian slasher,42In the following interview with Shahram Mokri in Persian, Mokri states that with Fish and Cat he intended to make a ‘slasher’ film and notes his interest and enthusiasm for slasher films. See “An Interview with Shahram Mokri,” www.youtube.com/watch?v=f7NtIyKWZ68 (accessed July 09, 2022). but it is a slasher without any slashing. Fish and Cat is formally innovative and is among a handful of films in the world to be shot in a single long take, such as Bela Tarr’s Macbeth (1982) and Alexander Sokurov’s Russian Ark (2002). The camera follows elliptically a number of students in the camp who have traveled to the Caspian region to participate in a kite-flying competition during the winter solstice. Nearby their camp is a small restaurant, whose three cooks seem to be serial killers using human meat for their restaurant. They are out on the hunt for new meat for their restaurant with plenty of students around to serve as the next meal. The film never actually shows a single murder, and throughout, the film is pervaded by an eerie sense of looming violence, a violence that always remains virtual but is never actualized on screen. The constant threat or virtuality of violence in the film creates a profound sense of terror and anxiety that metaphorically comments on the way Iranian society is under a constant threat of violence from state authority. This is the structure of symbolic authority as such, for, in order for it to “function as an effective authority, it has to remain not-fully-actualized, an eternal threat.”43Slavoj Žižek, Organs without Bodies: On Deleuze and Consequences (New York and London: Routledge, 2004), 4. This is precisely why the brief actualization of violence by the state in June 2009 in Tehran was so traumatic; but on the other hand, whenever the threat of symbolic authority passes from virtuality to actuality, the true impotence of its power is displayed. This is the moment of emancipatory consciousness, to see that beneath the façade of its power and authority: the “emperor has no clothes.” The circular temporal logic operative in the film has interestingly been read by Max Bledstein through the prism of taʻziyah—the dramatic passion play on the martyrdom of the third Shi’i Imam Hussein in Karbala, and his family. However, Mokri himself has cited the influence of the drawings of M.C. Escher on the circular temporality of the film as one single shot, stating “I wondered if it was possible to apply what Escher was doing in the medium of cinema, and create and impossible temporal perspective that occurs in one shot.”44[1]“The Time Bending Mysteries of Shahram Mokri,” www.youtube.com/watch?v=U6wfPMxdeRA (accessed July 09, 2022).

Fish and Cat (2013)

Mokri’s next film, the postapocalyptic crime vampire film Hujūm (Invasion; 2017), also fits within the coordinates of the uncanny between the weird and eerie, and it continues his engagement with the horror genre. Contra Fish and Cat, “Mokri himself has acknowledged the influence of the ta’ziyeh on… Invasion (2017).”45Max Bledstein, “Allegories of Passion: Ta’ziyeh and the Allegorical Moment in Shahram Mokri’s Fish and Cat,” MONSTRUM 4 (October 2021), 106. Within the setting of a stadium engulfed in perpetual darkness, there are men with strange tattoos who are engaged in a sport that remains unseen and unnamed. After the discovery of a body in the stadium, the police have mysteriously already identified the murderer. There only remains the circumstances of the crime, which has to be reconstructed in order for the case to be put to rest. But it is here that the true killer and his teammates want to take advantage of the reconstruction to commit another murder—the would-be candidate the twin sister of the victim, who is thought to be a vampire. However, in the midst of the re-enactment of the murder, the team players forget their supposed roles, chaos ensues, and the characters are caught in an endless loop, in which events repeat themselves in slightly different ways. As the write-up for the film in the Berlinale states, “The disquieting feeling that time is dissolving, that past, present and future are becoming one and that history has been halted is likely to strike a chord with how many young Iranians feel about their lives. Shahram Mokri’s intimate drama ominously interweaves place, space and time in the stadium’s labyrinthine corridors to form a dark allegory.” In an interview for the film, Mokri himself relates the film’s threatening and nightmarish atmosphere to contemporary Iran, sating: “I think this movie, [has] the same atmosphere in Iran these days.”46“The Filmmakers @ KVIFF 2018: Interview with Shahram Mokri,” YouTube, Jul 7, 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=zkxIg5yed9k (accessed January 19, 2020). Indeed, both Fish and Cat and Invasion evoke the dark, menacing, and threatening atmosphere of post-2009 Iranian society.

Another important film that may be emblematic of the rise of these horror inflected films deploying the two modes of the weird and the eerie is ‘Ali Ahmadzadeh’s nightmarish and ‘surreal’ road film Atomic Heart (Qalb-i atomi; 2015), also called Atomic Heart Mother (Mādar-i qalb atomi). The reason why this film is perhaps even more emblematic of the movement of the New Iranian Horror is because it contains some of the thematics of the New Iranian Horror delineated earlier, especially through unique deployment of occult motifs, in particular its evocation of the figure of the Devil or Satan. The film is structured into two halves with the first half apparently functioning as reality and the second half as surreality. This double or two-part structure of the film can be turned around through Lacan’s theory of fantasy and desire, where the first part of the film functions as the world of fantasy and the second part as the world of desire. It is in the second half, when reality loses its grounding in the world of fantasy, that we are confronted with the traumatic (Lacanian) Real in all its horror in the figure of Toofan, whose link with totalitarian and dictatorial figures (Saddam, Hitler) represents the Islamic Republic, and the Iranian president Mahmud Ahmadinejad. Nobahar and Arineh, the two female heroines of the film, may be lesbians whose homoerotic desire functions as the fright of Real desires in Lacanian terms, since in the Islamic Republic same-sex desire is forbidden and may bring one into confrontation with the Law, exemplified here in the figure of Toofan. It is this oppressive, sinister, and menacing atmosphere in Iran that this film so powerfully stages, and which is what all the films related to this emerging new movement have in common.47Also see the recent chapter on Atomic Heart by Shohini Chaudhuri which expands on my arguments apropos the weird and the eerie. Shohini Chaudhuri, Crisis Cinema in the Middle East Creativity and Constraint in Iran and the Arab World (United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Academic, 2022). See especially chapter 9.

Some of the horror films which represent lower quality commercial films that were produced for Iranian audiences and represent examples of the rise in popularity of the horror genre during this period include Mehrdad Mirfallah’s Khab-i Layla (Leila’s Dream; 2010), Nima Farahi’s Zar (2017), Farid Valizadeh’s The Mirror of Lucifer (2016), and Āl (2010) by Bahram Bahramian. Indeed, Bahramin’s Āl is an early proto example of the weird and the eerie horror sub-genre, since the figure of Āl and its subject matter, places it within the thematic coordinates of this movement. Similarly, and in addition to containing occult practices such as a séance and Spiritism, Farahi’s Zār deploys the supernatural wind or zār—a motif that also appears in transnational examples as a way to evoke the paranoid, threatening, and menacing atmosphere of post-2009 Iranian society. The film was initially given a permit for shooting and was self-funded by the director, but following its initial release, the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance did not grant a screening permit for the film, which was deemed unworthy of screening. After three years of being given the runaround, Farahi was finally able to secure a permit for screening the film and was inexplicably permitted to screen the film in cinemas. Zār was uploaded on YouTube so that Iranian audiences both at home and abroad could access the film for free without any hinderance.

As indicated above, Iranian horror films are not only emerging out of Iran but from the Iranian diaspora, especially from Iranian directors working in the US and Europe. One of the first diasporic or accented filmic examples that I situate as part of the transnational circuitry of New Iranian Horror is A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night (2014), Ana Lily Amirpour’s black-and-white vampire film made in the US. Though A Girl draws from the history of the vampire genre in both Anglo-American and European fiction and cinema, the film also taps into the vast reservoir of Iranian folklore and myths about a female vampire-like creature, namely the figure of bakhtak or kabus, otherwise known as the Nightmare. The film may be regarded among the new cycle of films that represents the uncanny between the weird and the eerie, in that it stages the return of the repressed Real of feminine sexuality, where the figure of the black chador-clad female vampire stands for the (Lacanian) Real of feminine sexuality, which in Islamic and Shi‘ite legal theory (fiqh) is imagined to possess an inherent surplus enjoyment (jouissance) that can cause chaos and destabilize the social-symbolic order—hence, the logic of the veil, which is meant to cover over this excess in feminine desire as a way to contain and control it. In this sense, the feminine body and female sexuality unimpeded functions as a source of terror to the ideology of the Islamic Republic. The film therefore stages the return of the repressed desire embodied in the chador-clad female vampire, the Girl, who hunts the male inhabitants of Bad City, representative of the dark underbelly of Tehran. There is a revolutionary core at the heart of the film where the vampire Girl stands for the call to all women to revolt against the patriarchal symbolic order, exemplified in the State and all its super-ego injunctions that seeks to control and delimit female autonomy and agency. In this way, and although the film was made outside Iran, it is a veritable commentary on the oppressive and repressive measures that are prevalent in contemporary Iran.48See Farshid Kazemi, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2021).

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014)

The chador-clad female vampire, the ‘Girl’ in A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014)

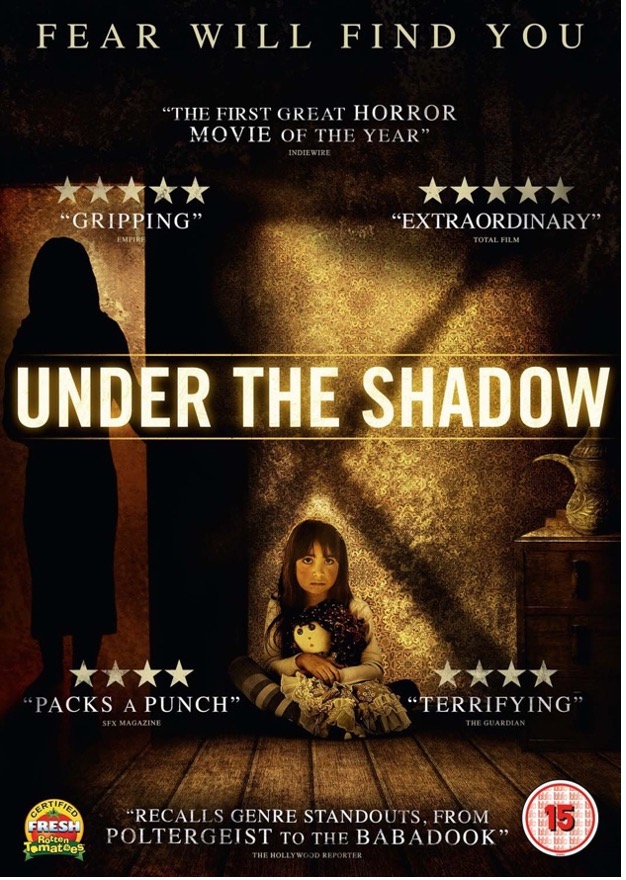

Perhaps inspired by the success of A Girl, another critically acclaimed diasporic Iranian horror film was made in the recent past, this time in the UK, namely, Babak Anvari’s Under the Shadow (2016).49During the question and answer session following the premiere screening of Under the Shadow at the Cameo Cinema in Edinburgh in 2016, I asked Babak Anvari whether A Girl or any other Iranian horror films were an influence on his film. Although he was not very forthcoming on the influence of A Girl, but mentioned the Iranian horror film Girl’s Dormitory. For other filmic and directorial influences both Western and Iranian, see “Under the Shadow: The Films that Influenced this Creepy Iranian Horror,” interview by Samuel Wigley, Updated: 13 February 2017, accessed April 25, 2017, www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/news-bfi/interviews/under-shadow-babak-anvari-influences-iranian-horror. The film is set during the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988), and centers on the life of a married couple, Shideh and Iraj, and their young daughter Dorsa. After the father (Iraj), who is a doctor, leaves to offer medical aid at the frontlines, an Iraqi missile hits the roof of their apartment building but does not explode—a scene that seems to have been inspired by The Devil’s Backbone (2001), the Spanish-Mexican ghostly horror film directed by Guillermo del Toro. It is after this incident that the daughter and mother are haunted by the appearance of the jinn (as noted above, jinn folklore was also used in the Girl’s Dormitory), who relentlessly attack them until they finally escape their building. There is a formal connection made in the film between the unexploded missile and the appearance of the female jinn (a similar connection is drawn in The Devil’s Backbone between the unexploded bomb and the appearance of the ghost) on the building that serves as a political allegory for the horrors of the Iran-Iraq War, and the nightmarish universe created by the new Islamic regime after the Revolution. The influence on the film of the motif of zār, or malefic wind, in southern Iranian folklore is also evident, especially as much of the imagery linked to the jinn is gestured through the motif of the wind, and is related to beliefs pertaining to zar.50“Zār, harmful wind (bād) associated with spirit possession beliefs in southern coastal regions of Iran. In southern coastal regions of Iran such as Qeshm Island, people believe in the existence of winds that can be either vicious or peaceful, believer (Muslim) or non-believer (infidel). The latter are considered more dangerous than the former and zār belongs to this group of winds.” Maria Sabaye Moghaddam, “ZĀR,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, accessed October 22, 2016, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/zar

Under the Shadow (2016)

The trend of making horror films within transnational circuitry continues with another film called Shab (The Night; 2019/2020), directed by Kourosh Ahari. Perhaps influenced by the successes of Amirpour’s A Girl and Anvari’s Under the Shadow, The Night went into production in the US in 2018 and was mainly shot on location in that country. The Night stars Cannes Best Actor winner Shahab Hosseini, as well as Niousha Jafarian, in lead roles. The film has a higher production value than its other diasporic counterparts but is similarly populated by a cast consisting predominantly of Iranian immigrants or US-born Iranian-Americans. Like A Girl and Under the Shadow, the film’s dialogue is mostly in Persian and the majority of the people who worked on the film were either Iranian or of Iranian descent. The film was given permission for screening in Iran, which is unprecedented in the history of films made by Iranian filmmakers outside Iran. The film can be seen to fit well within the coordinates of the New Iranian Horror cinema since it evokes the logic of the double or the doppelgänger, especially in one of the last scenes of the film where Shahab Hosseini’s character looks into the mirror and his mirror-image suddenly splits off from him and acts autonomously. This double is the traumatic repressed which returns to haunt us in the Night(mare). This structure of the double, which is repeated throughout the film, both at the level of form and narrative, gestures to one of the characteristics of life in contemporary Tehran under the Islamic Republic, namely the double-life led by many of its subjects. This structure of a double-life, where you dissimulate the truth in order to survive is part of the technique of taqīyah (dissimulation) in Shi’ite doctrine, which has permeated social and political relations in Tehran.51On taqīyah in Shi‘ism see Etan Kohlberg,“Some Imami-Shi‘i Views on Taqiyya,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 95, 3 (July-September 1975): 395-402; Etan Kohlberg, “Taqiyya in Shi‘i Theology and Religion,” in Secrecy and Concealment: Studies in the History of Mediterranean and Near Eastern Religions, ed. Hans Hans Gerhard Kippenberg, Guy G. Stroumsa (Leiden: Brill, 1995), 345-80. L. Clarke, “The Rise and Decline of Taqiyya in Twelver Shi‘ism,” in Reason and Inspiration in Islam: Theology and Inspiration in Islam, ed. Todd Lawson (London: I.B. Tauris Publishers, 2005), 46-63. Due to the strict controls, surveillance, and policing of society by the State apparatus, Iran is a Janus-face society, with everyone leading a double-life as a survival strategy.52On the Janus-face society in Iran, see Ramita Navai, City of Lies: Love, Sex, Death, and the Search for Truth in Tehran (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2014), 1. The title of the film, Night, itself symbolizes a never ending night or perpetual darkness that has enveloped Iranian society, with the hotel in which the couple are effectively imprisoned standing for Iranian society under the Islamic Republic. In this sense, the film enacts a subtle critique of the State by deploying the conventions of psychological horror.

The Night (2020)

It should be noted that the New Iranian Horror is not confined only to feature films but comprises the burgeoning of new shorts and animation films that can be said to constitute this larger growing body of Iranian horror films that I have termed New Iranian Horror. For example, a notable and beautiful animated short that may be mentioned is Malakout (2020) written and directed by Farnoosh Abedi. The film was part of the official selection at the online Halloween Film Festival 2020. The short uses to powerful effect elements of expressionism (shadows, chiaroscuro lighting) and the Gothic—evocative of the stop-motion animation of Tim Burton in such films as Vincent (1989) and Corpse Bride (2005)— especially the setting of a large Qajar mansion and the iconography of late nineteenth century Iranian art. In fact, the film is largely based on the German expressionist silent horror film, The Hands of Orlac (1924), directed by Robert Wiene who also directed the silent horror, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), perhaps one of the most influential films of German expressionism. The short depicts a mourning pianist who grieves the loss of his wife, and who, longing to bring his wife back from the dead, is visited by the figure of Death, to whom, in a Faustian bargain, he sacrifices his hands for the return of his love. Another noteworthy short is Hiyvān (AniMal; 2017), directed by the Ark brothers, Bahman and Bahram Ark. The short depicts a person who, while attempting to cross a border, is forced to metamorphose into a ram (the iconography of the ram also evokes the ram’s occult and magical associations) by using the animals head as a disguise, gesturing towards the dark and animalistic treatment of immigrants and their plight, but also what Iranian migrants have to go through in order to escape Iran. Although some of the feature horror films or shorts may not contain a critico-political subtext and may be seen as the directors’ interest in the horror genre itself, the larger growing popularity in productions of the horror genre in Iran and in the diaspora may be read as part of a response in the aftermath of the failed protest movement and the subsequent terrifying and fearful atmosphere that permeates post-2009 Iranian society.

Malakout (2019)

Screenshot from Malakout (2019)

The Ark brothers (Bahman and Bahram Ark), made their first feature debut with the magical fantasy-horror film, Pūst (Skin; 2020). A supernatural curse follows the son of a family, whose mother is threatened by the jinn, since she had cast a spell on a woman whom her son loved and by doing so, sought to thwart their union. The film uses aspects of magical beliefs and folktales from Azerbaijan with the films dialogue itself being in Azeri. The film was never given screening permission in Iran and does not appear to have been entered into any of the international film festivals. The film showcases the talents of the Ark brothers in the making of genre pastiches that include elements of horror.

An Iranian filmmaker whose films appear in the International Film Festival circuits and whose recent films play with horror genre tropes is Mani Haghighi. The mystery supernatural horror thriller A Dragon Arrives (Izhdihā vārid mīshavad; 2016), is perhaps Haghighi’s first foray into supernatural territory. The film was selected for competition for the Golden Bear at the 66th Berlin International Film Festival. The film is shot in part as a mockumentary and in part as supernatural mystery—the mystery being related to the death of the political prisoner who lived in a shipwreck in the middle of the desert, the cause of which may or may not be a jinn. The jinn is never shown in the film but only appears as a narrative MacGuffin. The film draws inspiration from Bahram Sadeqi’s novella Malakūt (Heavenly Kingdom)—adapted into a film by Khosrow Haritash in 1976—in which the first famous line of the book is recited in the film, “At eleven, on the Wednesday evening of that week, Mr. Maveddat was possessed by the jinn.” Sadeqi’s book even appears in the mise-en-scène of the film and functions as a form of filmic intertextuality that calls attention to the relation between this text and the film. Haghighi’s recent comedy-horror Khūk (Pig; 2018) is ostensibly a spoof of serial killer films, in which there is a mysterious serial killer who calls himself the Pig, and who is stalking and killing directors. A blacklisted director named Hasan Kassami (Mohammad Hassan Madjooni) is feeling a sense of neglect and wonders why the serial killer has not come after him and complains humorously to his mother in one scene, “If he had cut off my head, they wouldn’t disrespect me.” To which his mother coyly replies, “Don’t worry my son, he’ll come after you [too]…” The film is not only a critique of the commercial film industry in Iran, but also of the Islamic Republic, which stands in for the serial killer who target certain filmmakers that are critical of the regime.

Apropos serial killer films, there is what may be termed a ‘serial killer turn’ in Iranian cinema with the recent release of two films, based on the real-life serial killer Saeed Hanaei who murdered sixteen prostitutes, in the Shi’i holy city of Mashhad from 2000 to 2001.53There is also a graphic novel by the exiled cartoonist Mana Neyestani, titled The Spider of Mashhad (2017) and based on video interviews with the serial killer. The first film, titled Killer Spider (Ankabūt; 2020), is directed by Ebrahim Irajzad. The film is a dramatic social critique with little horrific elements and does not show overt scenes of killing, blood, or violence but only hints at them through camera techniques suggesting violence outside the frame—one of the few strategies available to filmmakers making horror in postrevolutionary Iran, so as not to run afoul of the censors. Holy Spider (2022), the other film based on the same serial killer, is by the Iranian-Danish director Ali Abbasi. Upon premiering at the Cannes Film Festival, it was given a seven-minute standing ovation. The film was shot in Jordan with the entire dialogue in Persian, as in other examples of diasporic horror films. The film follows a female journalist Rahimi (Zar Amir-Ebrahimi)—winner of the Best Actress award at Cannes for her performance in the film—who is trying to crack the case but is thwarted at every turn by the apathy of the authorities. It is revealed, however, that the killer is an Iran-Iraq War veteran by the name of Saeed (Mehdi Bajestani), who lives a seemingly normal family life but who picks up drug addicted women or prostitutes at night on his motorcycle and remorselessly strangles them as a way to religiously cleanse the world. The movie stages brutal violence and sex scenes that could not otherwise have been shown if the film had been made in Iran. The film recalls serial killer films such as Bong Joon-ho’s Memories of Murder (2003) and David Fincher’s Zodiac, which were also based on real-life serial killers. Holy Spider is a powerful socio-political critique of a society that gave birth to such a heinous killer who not only justified his horrific actions based on religious beliefs, but whose victims were destitute women that were forced to sell their bodies to support themselves and their children, and who were ignored in Iranian state media of the time that reported on the killings. The burgeoning of such films metaphorically suggests that the ‘true’ serial killer in these films is the Islamic Republic itself.

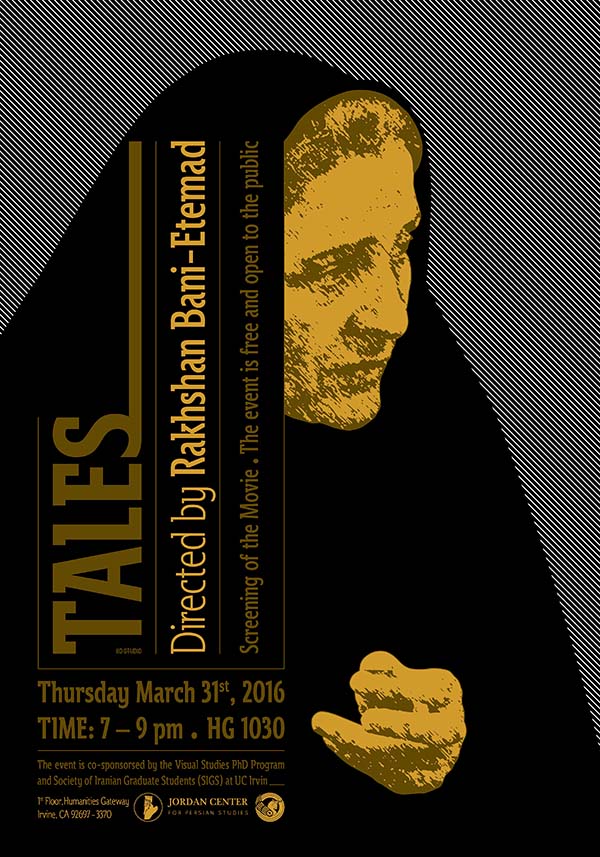

Continuing this trend of prestige horror films is a recent film which has won international acclaim, namely the horror-comedy Zālāvā (2021), directed by Arsalan Amiri and co-written with Ida Panahandeh and Tahmineh Bahramalian. The film was screened at the 39th Fajr Film Festival and was also part of the Toronto International Film Festival’s Midnight Madness. The film is set in Zalava, a village of the Kurdistan region of Iran, in 1978, just before the Iranian Revolution. After reports of jinn possession in the village reaches the authorities, a skeptical Gendarmerie sergeant Masoud (Navid Pourfaraj), is sent to investigate the situation. The villagers fear that Zalava was cursed, and that demonic entities or jinn exist in their midst. Alarmed by this superstition, the villagers want to exorcize the suspected victim of possession by employing a crude method such as resorting to bloodletting with their rifles—a possibly lethal form of exorcism. After the onset of the death of a supposed victim of possession, the incident brings into confrontation Masoud and the local shaman or ramal (jinn-catcher), Amardan (Pouria Rahimi Sam), who claims that he can permanently contain the demonic plague that has beset the village. The film puts a modern twist on the fabled ‘Genie in the Bottle’ motif from the Thousand and One Nights. As critic Peter Kuplowsky states, “this dread-filled fable eventually crystalizes these tensions in an irresistible, metaphysical horror dilemma that is guaranteed to haunt you the next time you handle a sealed glass jar, regardless of whether a demon waits inside.”54Peter Kuplowsky, “Zalava,” accessed June 20, 2020, https://tiff.net/events/zalava Zālāvā was made during the global COVID-19 pandemic and comments on current fears and anxieties about the virus and its societal effects, all the while critically engaging with questions of reason and superstition, tradition and modernity.

Zālāvā (2021)

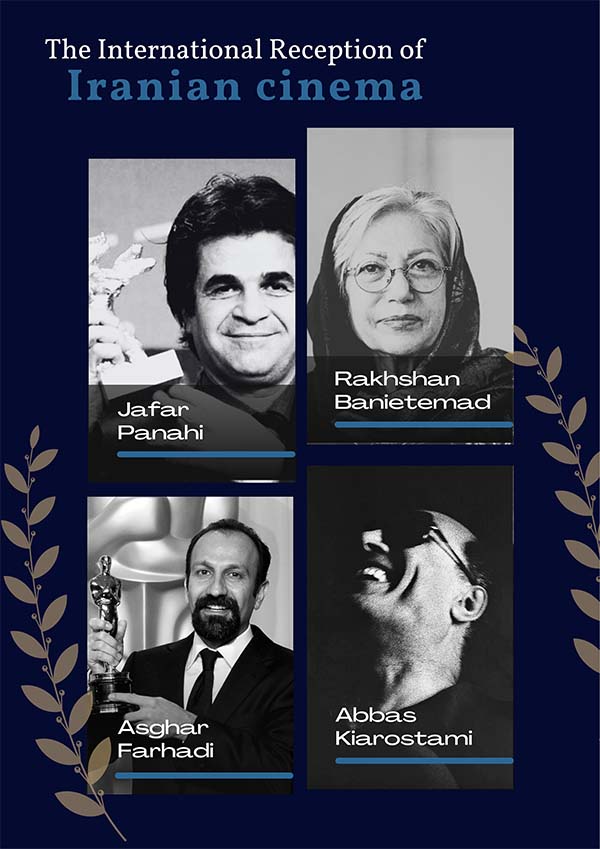

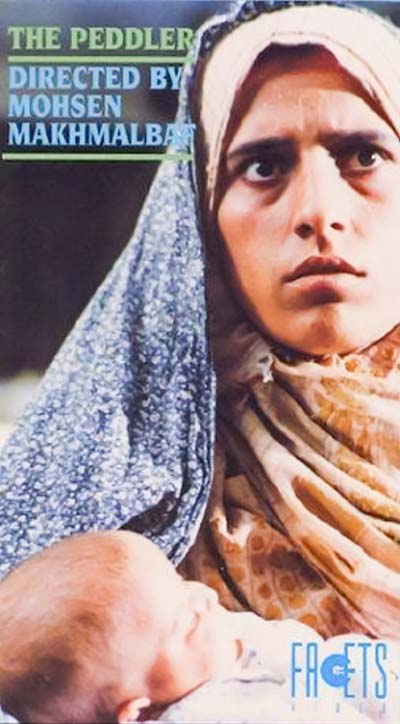

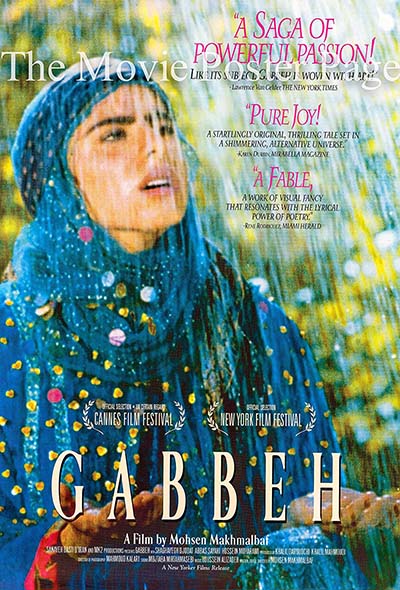

As noted, there is, in the films that are emerging from Iran today, a notable shift from the arthouse films of the New Iranian Cinema that used to populate and dominate international film festivals, and which were directed by the likes of Kiarostami, Makhmalbaf, Panahi, Rasoulof, and Ghobadi—a shift which was even noted by the film scholar Kristin Thompson in her review of Iranian films at the Vancouver International Film Festival in 2014, which included A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014) by Ana Lily Amirpour and Shahram Mokri’s Māhī va gurbah. Kristin Thompson states: “Maybe it’s just the particular selection of Iranian films at this year’s festival, but I sensed a shift from the ones we’ve seen in previous years…. all three of the Iranian fiction features this year depart from some conventions we’ve grown used to in the New Iranian Cinema of the past decades.”55See Kristian Thompson, “Iranian cinema moves on,” Thursday, October 9, 2014, accessed May 25, 2016, www.davidbordwell.net/blog/2014/10/09/middle-eastern-fare-at-viff/ Zālāvā seems to be continuing this trend with the recent growth of prestige or high-quality horror films emerging both from within Iran and from the Iranian diaspora. To conclude, it remains to be seen if the New Iranian Horror Cinema will continue unabated within the transnational circuitry, with new films and filmmakers joining the fray, or if it will be stifled with new censorship measures that will halt its development and progress. Regardless, a new era of Iranian cinema has already been born and will require sustained theoretical attention by film scholars and critics.